Today, I’m doing a quick blog that will hopefully distract

you from the Jeter love-fest that’s been going on. Don’t forget, there is another dude retiring –

Paul Konerko. Konerko has been a solid,

consistent player for the past 15 years with the Chicago White Sox. While I don’t really have time to go into a

full on examination of his career, I wanted to find out if Paul Konerko was a

Hall of Famer. I really wanted it to be

closer, but when you compare against a few other players, the answer is a solid

probably not.

Comparing him against fellow White Sox' teammate and Hall of Famer Frank Thomas, Hall of Fame hopeful but probably not Fred McGriff, another fellow White Sox' teammate Jim Thome, and Hall of Famer Johnny Mize, you can see that Konerko doesn't really stack up against those guys.

Konerko just didn't have the combination of things that really puts some of these other guys over the top. He didn't hit 500 home runs. That's not necessarily an automatic entry into the hall nowadays, but it certainly would have helped. He didn't strike out an excessive amount - his career high was 117 in 2004 - but that being the case, the voters probably would want a higher batting average.

Mize didn't get into the hall through regular voting. He was elected by the Veteran's Committee. You have to remember that Mize lost three full seasons to military service though. And look at that strikeout to walk ratio.

In 1998, the Cincinnati Reds traded Konerko to the White Sox for Mike Cameron. What if instead the Reds had traded him to the Yankees? Maybe for Ricky Ledee? Come on Reds fans, doesn't that sound like a trade they would make? Or maybe for Paul O'Neill. Bring him back to Cincinnati to finish his career and provide some veteran leadership.

So, if Konerko went to the Yankees, would he be a Hall of Famer? The Tino Martinez era was pretty brief in New York. He would be gone by the end of 2001. The Yankees then wouldn't have had to sign Jason Giambi. Konerko would have just been able to hit in the best lineup in the first half of the 2000's. He almost certainly would have had better numbers, and the shine associated with playing in New York and the number of World Series rings would had definitely bolstered his cause (Don Mattingly would like to point out that BOTH of those things are necessary).

No, Paul Konerko isn't a Hall of Famer. But let's not just sit back and watch #2 get all the glory these last few days of the season.

Friday, September 26, 2014

Thursday, September 25, 2014

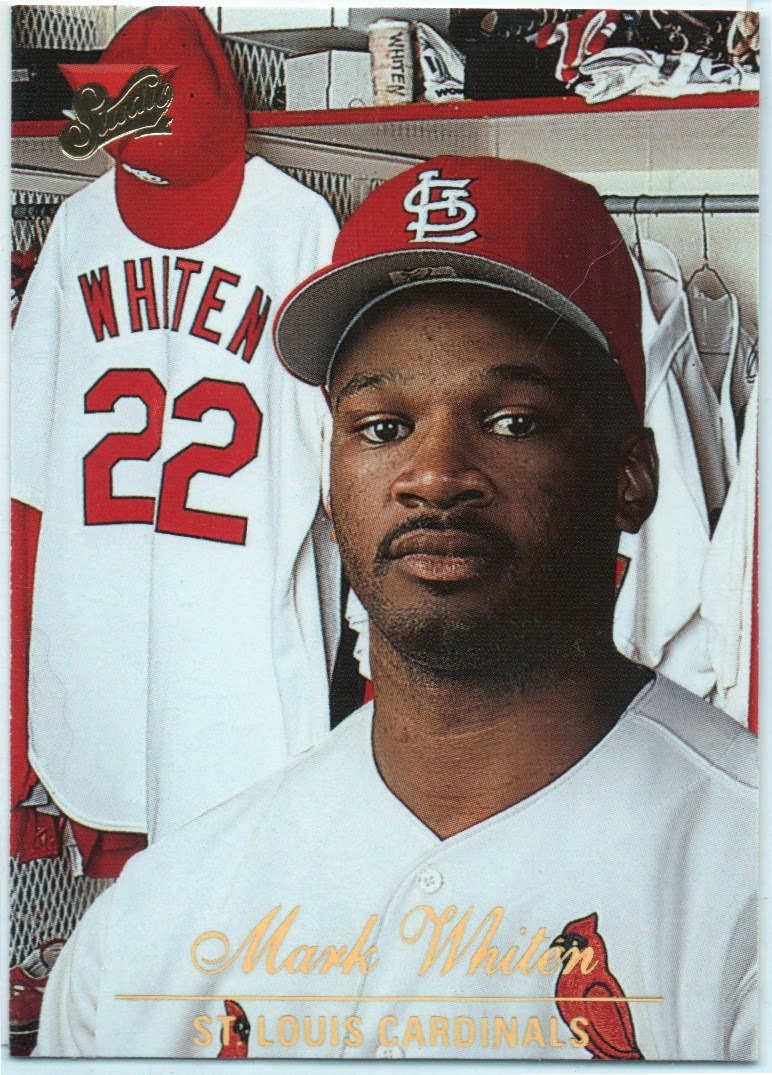

The Day Mark Whiten and Lonnie Maclin Set Career Highs

Being a St. Louis Cardinals fan, there’s not much that I

care to remember from the early 1990’s.

But there’s one thing that I’ll never forget, and that’s Mark Whiten’s

four home run game on September 7th, 1993.

Being a St. Louis Cardinals fan, there’s not much that I

care to remember from the early 1990’s.

But there’s one thing that I’ll never forget, and that’s Mark Whiten’s

four home run game on September 7th, 1993. This was actually the second game of the day. The Cardinals lost the first game 14-13 to

the Cincinnati Reds. In the top of the

eighth, the Cardinals exploded for seven runs, turning a 9-6 deficit into a

13-9 lead. They actually had runners at

second and third base with one out with seven runs in, but for some reason,

Stan Royer didn’t attempt to score on Tripp Cromer’s groundout to second, and

then Luis Alicea struck out looking to end the inning. Actually, I think I remember that exact

scenario unfolding watching the Louisville Redbirds in 1989. Anyway, Mark Whiten had a small part in the

eighth inning action, drawing a bases loaded walk off of Scott Ruskin, scoring

Gregg Jefferies, earning his first RBI on the day.

This was actually the second game of the day. The Cardinals lost the first game 14-13 to

the Cincinnati Reds. In the top of the

eighth, the Cardinals exploded for seven runs, turning a 9-6 deficit into a

13-9 lead. They actually had runners at

second and third base with one out with seven runs in, but for some reason,

Stan Royer didn’t attempt to score on Tripp Cromer’s groundout to second, and

then Luis Alicea struck out looking to end the inning. Actually, I think I remember that exact

scenario unfolding watching the Louisville Redbirds in 1989. Anyway, Mark Whiten had a small part in the

eighth inning action, drawing a bases loaded walk off of Scott Ruskin, scoring

Gregg Jefferies, earning his first RBI on the day. The Reds would score three runs in the bottom of the eighth

off of a Dan Wilson bases loaded single and a Jack Daugherty sac fly. Jefferies would single, steal a base, and

advance to third on a sac fly in the top of the ninth, but he was stranded there

after Jeff Reardon got Bernard Gilkey to pop out to second base to end the

inning. In the top of the ninth, Jacob

Brumfield doubled with one out, and Hal Morris followed that with a walk. Reggie Sanders then finished it off of Todd

Burns with a triple to end the game.

Whiten quickly put his learnings from Pensacola Junior College to work,

deducing that the Cardinals would need to score more than 14 runs if they were

to win the nightcap. He sat down between

games with Lonnie Maclin and quickly went to work on a plan to do just that.

The Reds would score three runs in the bottom of the eighth

off of a Dan Wilson bases loaded single and a Jack Daugherty sac fly. Jefferies would single, steal a base, and

advance to third on a sac fly in the top of the ninth, but he was stranded there

after Jeff Reardon got Bernard Gilkey to pop out to second base to end the

inning. In the top of the ninth, Jacob

Brumfield doubled with one out, and Hal Morris followed that with a walk. Reggie Sanders then finished it off of Todd

Burns with a triple to end the game.

Whiten quickly put his learnings from Pensacola Junior College to work,

deducing that the Cardinals would need to score more than 14 runs if they were

to win the nightcap. He sat down between

games with Lonnie Maclin and quickly went to work on a plan to do just that. |

| This is beautiful. You can see all four levels of seats in old Cardinal Stadium. |

The Reds would keep the momentum from the first game going

in the bottom of the first. Thomas

Howard led off with a walk, followed by a double from Brumfield. Morris then hit a sac fly, scoring Howard,

and then Brumfield scored after stealing third and an error on the throw from

Pagnozzi. After that point, though, Bob

Tewksbury was pretty much lights out. He

went the distance, allowing no more walks or runs, and only six more hits. After the first inning, it was Cardinals 4,

Reds 2.

The next three innings were scoreless affairs, with a Maclin strikeout and Whiten pop out sprinkled in, so let’s fast forward to the fifth inning. In the top half of the frame, Tewksbury would lead off with his second walk of the day. He advanced to second on a wild pitch, and then Pena bunted him over. That’s when Maclin summoned his inner Whiten and hit a sac fly to center field, scoring Tewksbury. Brumfield would single off of Tewksbury in the bottom half of the inning, but that was it for the Reds. Cardinals 5, Reds 2.

The next three innings were scoreless affairs, with a Maclin strikeout and Whiten pop out sprinkled in, so let’s fast forward to the fifth inning. In the top half of the frame, Tewksbury would lead off with his second walk of the day. He advanced to second on a wild pitch, and then Pena bunted him over. That’s when Maclin summoned his inner Whiten and hit a sac fly to center field, scoring Tewksbury. Brumfield would single off of Tewksbury in the bottom half of the inning, but that was it for the Reds. Cardinals 5, Reds 2.

Mike Anderson relieved Reds starter Larry Luebbers to start

the sixth inning. Anderson promptly

walked Zeile and Perry to start the inning.

That’s when Whiten decided to get halfway to the home run cycle, hitting

a three run shot, giving him seven RBIs on the day to that point. Rounding the bases, he gave a big salute to

Maclin, as they were now over halfway to their goal of scoring more than 14

runs. With tears in his eyes at the

beauty of the unfolding plan, Pagnozzi grounded out to short. Cromer and Tewksbury went down quietly as

well, and the Reds failed to make any noise in the bottom of the frame. Cardinals 8, Reds 2.

Anderson remained in the game to start the top of the

seventh inning for the Reds. After Pena

struck out, Maclin fouled out to third base.

Shamed by this, Maclin hung his head and went back to the dugout. Whiten, always a

glass-two-thirds-of-the-way-full kind of guy, told him to keep his head up, and

actually ordered some nachos for him from a vendor close by. While this was happening, Gilkey and Zeile

singled, setting up Perry for an RBI single.

Whiten, batting gloves still slathered in nacho cheese, deposited another

ball over the wall, giving him three home runs and 10 RBIs on the day to that

point. While running around the bases,

Whiten spelled out M-A-C-L-I-N, YMCA-style.

Anderson remained in the game to start the top of the

seventh inning for the Reds. After Pena

struck out, Maclin fouled out to third base.

Shamed by this, Maclin hung his head and went back to the dugout. Whiten, always a

glass-two-thirds-of-the-way-full kind of guy, told him to keep his head up, and

actually ordered some nachos for him from a vendor close by. While this was happening, Gilkey and Zeile

singled, setting up Perry for an RBI single.

Whiten, batting gloves still slathered in nacho cheese, deposited another

ball over the wall, giving him three home runs and 10 RBIs on the day to that

point. While running around the bases,

Whiten spelled out M-A-C-L-I-N, YMCA-style.Surprisingly, Whiten’s third dinger of the day didn’t knock Anderson out of the game. That came a batter later, when Pagnozzi singled. Chris Bushing entered the game and retired Cromer to end the top of the inning. Brian Dorsett would pinch hit and single for Bushing in the bottom of the inning, but that was it for the Reds. Cardinals 12, Reds 2.

Rob Dibble entered the game in the top of the eighth for Cincinnati. Tewksbury struck out before Pena swelled up and hit a home run. Maclin was the next batter, but the only thing that he could do was ground out to second. Maclin was no Whiten. He knew it, Whiten knew it, the nacho vendor knew it. At that point, Whiten autographed his cleats and gave them to Maclin (they weren’t actually his cleats; they were Jim Lindeman’s cleats from 1989 that fell behind the industrial washing machines). The Reds couldn’t get anything going in the bottom of the eighth. Cardinals 13, Reds 2.

Dibble remained in the game in the ninth. Royer struck out to start the frame, but then Perry singled to center field. Whiten

came up and did the only thing he could do.

He hit a home run. He rounded the

bases cleatless, wanting Maclin to believe that he actually gave him his cleats

an inning earlier. Whiten now had four

home runs and 12 RBIs on the day, and the plan that he and Maclin sat down and

concocted had come to fruition. They had

scored more than 14 runs. Whiten was the

last baserunner of the day for either team.

The Cardinals won 15-2.

Dibble remained in the game in the ninth. Royer struck out to start the frame, but then Perry singled to center field. Whiten

came up and did the only thing he could do.

He hit a home run. He rounded the

bases cleatless, wanting Maclin to believe that he actually gave him his cleats

an inning earlier. Whiten now had four

home runs and 12 RBIs on the day, and the plan that he and Maclin sat down and

concocted had come to fruition. They had

scored more than 14 runs. Whiten was the

last baserunner of the day for either team.

The Cardinals won 15-2.Whiten and Maclin both achieved career highs that day for RBIs in a game. Maclin’s one RBI was the only RBI of his career. Whiten’s 12 RBIs tied fellow Cardinal Jim Bottomley for most in a game in major league history. He also tied the Padres’ Nate Colbert for most RBIs in a double header with 13. His four home runs also tied several players for most in a game.

Whiten set career highs in 1993 in games played, at bats, runs, hits, home runs and RBIs. He was also player of the week twice that season. The first time was the week of July 18th when he hit .385 with three home runs and nine RBIs (this was in four games in the short week of the All Star game). And of course, the second time was the week of September 12th, when he hit .321 with four home runs and 14 RBIs.

|

| And thaaat was a 70 MPH fastball. |

With 105 career home runs, only three other players who have

hit four home runs in a game have few than him.

Two of those players (Bobby Lowe and Ed Delahanty) accomplished the feat

in the 19th century, and the other one did it in 1948 (Pat Seerey). Of all of the players with 10 or more RBIs in

a game, only Phil Weintraub and Norm Zauchin have fewer RBI’s than Whiten’s

career total of 423.

With 105 career home runs, only three other players who have

hit four home runs in a game have few than him.

Two of those players (Bobby Lowe and Ed Delahanty) accomplished the feat

in the 19th century, and the other one did it in 1948 (Pat Seerey). Of all of the players with 10 or more RBIs in

a game, only Phil Weintraub and Norm Zauchin have fewer RBI’s than Whiten’s

career total of 423. Lastly, I would like to bring up the record for most RBIs in

a game where a player accounted for all of his team’s runs. That feat was accomplished by Mike Greenwell

on September 2nd, 1996.

Greenwell knocked in all nine of the Red Sox’ runs in a 9-8, 10 inning

victory over the Seattle Mariners.

Manning left field for the Mariners that day? Mark Whiten.

Lastly, I would like to bring up the record for most RBIs in

a game where a player accounted for all of his team’s runs. That feat was accomplished by Mike Greenwell

on September 2nd, 1996.

Greenwell knocked in all nine of the Red Sox’ runs in a 9-8, 10 inning

victory over the Seattle Mariners.

Manning left field for the Mariners that day? Mark Whiten.Sunday, September 21, 2014

DONT WALK

Being somewhat of a grammar nazi, I’ve always looked at the

“Walk/Don’t Walk” sign with a bit of sadness.

There’s no apostrophe in the “Don’t”, I’m not sure who to tell, and it

probably wouldn’t matter anyway. I get

that there’s space consideration there, but couldn’t you just cut out an

apostrophe in the black? Isn’t there

just one big red light illuminating a cutout?

I don’t know. And nowadays, the

public schools have gotten so bad, they just go with white and red people. You don’t even have to read! But this is a baseball blog (hopefully fairly

grammatically correct). We’re not here

to talk about apostrophes. Today, we’re

going to talk about someone who took the DONT WALK sign to heart, Dan

Quisenberry.

Being somewhat of a grammar nazi, I’ve always looked at the

“Walk/Don’t Walk” sign with a bit of sadness.

There’s no apostrophe in the “Don’t”, I’m not sure who to tell, and it

probably wouldn’t matter anyway. I get

that there’s space consideration there, but couldn’t you just cut out an

apostrophe in the black? Isn’t there

just one big red light illuminating a cutout?

I don’t know. And nowadays, the

public schools have gotten so bad, they just go with white and red people. You don’t even have to read! But this is a baseball blog (hopefully fairly

grammatically correct). We’re not here

to talk about apostrophes. Today, we’re

going to talk about someone who took the DONT WALK sign to heart, Dan

Quisenberry.

Quisenberry signed with the Kansas City Royals as a free

agent in June of 1975, out of the University of La Verne in La Verne, CA. The Leopards have produced a total of 10

major league players, but Quisenberry is the last one to have played in the

majors.

Upon his signing, the Royals assigned Quisenberry to A ball

Waterloo. It was there where he would

make his only professional start, which just happened to also be a complete

game. Overall there, he would go 3-2

with a 2.45 ERA and four saves with 31 strikeouts vs. just six walks (one

intentional) across 44 innings in 20 games.

This earned him a promotion to AA Jacksonville to finish the 1975

season. There, he went 0-1 with a 2.25

ERA and one save with two strikeouts vs. four walks (one intentional) across

eight innings in six games.

The Royals would give Quisenberry the same schedule in

1976. Starting again at Waterloo, he

went 2-1 with a 0.64 ERA and 11 saves with 19 strikeouts and nine walks (four

intentional) across 42 innings in 34 games.

Those numbers, plus a WHIP of 0.881, earned him another promotion back

to Jacksonville. There, he went 0-1 with

a 2.25 ERA and six strikeouts vs. four walks (two intentional) across 12

innings in nine games.

Quisenberry would spend the next two seasons in

Jacksonville, where he would combine to go 7-3 with a 1.17 ERA and 21 saves

with 62 strikeouts vs. 23 walks (eight intentional) across 138 innings in 81

games. He would be promoted to AAA Omaha

for 1979, where he would go 2-1 with a 3.60 ERA and five saves, with 16

strikeouts vs. 10 walks (one intentional) in 35 innings across 26 games.

The Royals finally came to their senses in early July. Quisenberry was called up, and he made his

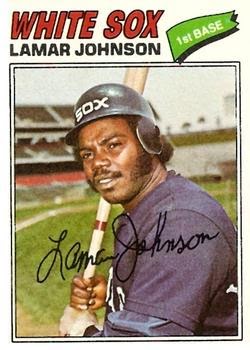

Major th, 1979. In a 4-2 loss to the Chicago White Sox, he

entered the game in the top of the seventh and induced a ground ball double

play off the bat of Lamar Johnson. In

the eighth, he allowed a single to Rusty Torres, who was quickly erased by

another ground ball double play off the bat of Greg Pryor. In the ninth, he allowed a double to Alan

Bannister amid three more groundouts. The

Royals tried to put something together in the bottom of the frame, with U.L.

Washington hitting a one out single to center field, but a Willie Wilson pop

out and George Brett ground out ended the day.

The Royals finally came to their senses in early July. Quisenberry was called up, and he made his

Major th, 1979. In a 4-2 loss to the Chicago White Sox, he

entered the game in the top of the seventh and induced a ground ball double

play off the bat of Lamar Johnson. In

the eighth, he allowed a single to Rusty Torres, who was quickly erased by

another ground ball double play off the bat of Greg Pryor. In the ninth, he allowed a double to Alan

Bannister amid three more groundouts. The

Royals tried to put something together in the bottom of the frame, with U.L.

Washington hitting a one out single to center field, but a Willie Wilson pop

out and George Brett ground out ended the day.

Quisenberry would pick up his first major league victory 14

days later in a 7-6 win over the Texas Rangers.

He allowed his first run in the bottom of the eighth, blowing the save,

but the Royals scored a run in the top of the ninth, and he shut the door in

the bottom of the frame. The next day,

he would get his first career save against the Rangers. Overall for his first half season in

baseball, one probably didn’t see this guy as a future dominant closer. He finished 3-2 with a 3.15 ERA and five

saves with 13 strikeouts vs. seven walks (five intentional) in 40 innings

across 32 games. He also added three

holds, but he had five blown saves. If

you look at his outings though, there were two instances where he gave up four

runs each in a total of three innings.

If you take those two outings out, his ERA falls to 1.46. In both of those outings, he allowed two home

runs. He only allowed one other home run

in the other 37 innings he pitched.

The 1979 Royals only had a total of 27 saves, and it took

six different pitches to achieve that total.

They finished the season 85-77, three games back of the California

Angels. If they were going to get over

the hump, they were going to need to do better than 27 saves. And so they did.

Quisenberry opened the 1980 season as the closer in Kansas

City, and never looked back. At the end

of May, he was having a pretty decent season, sitting at 3-2 with a 2.61 ERA

and eight saves. Two months later, at

the end of July, he was 7-4 with a 3.12 ERA and 20 saves. Then came August. He pitched in 18 games that month, going 4-1

with a 1.03 ERA and 11 saves, with only one blown save. The Royals were 16-2 in games in which he

pitched that month. He had 10 walks that

month, but seven of those were intentional, including three on the day where he

had his only blown save. He gave up a

run in the bottom of the ninth, allowing the Toronto Blue Jays to tie it at

three. Quisenberry would pitch FOUR MORE

INNINGS that day without allowing a run, before the Jays finally broke through

for a run in the bottom of the 14th inning off of Rawly

Eastwick. Shamed by the outing, Eastwick

would never pitch again for the Royals.

Quisenberry had a somewhat rough September, when he went 1-2

with a 5.48 ERA and only two saves. On September 4th, he allowed six runs on seven hits and a walk

(intentional of course) in a third of an inning in a 9-5 loss to the Milwaukee

Brewers. The Brewers scored eight of

those runs in the ninth inning off of nine singles and the intentional

walk. The Royals though accomplished

what they set out to do though. They had

a total of 42 saves on their way to a 97-75 record, finishing a full 14 games

ahead of the second place Oakland A’s.

They would sweep the Yankees in the ALCS before losing to the Phillies

in six games in the World Series.

Quisenberry was excellent in the ALCS, but struggled in the World

Series, allowing six runs in 10 1/3 innings, going 1-2 with a 5.23 ERA and one

save. Overall for the season, he was

12-7 with a 3.09 ERA and a league leading 33 saves with 37 strikeouts vs. 27

walks (15 intentional) in 128 1/3 innings across 75 games. He finished fifth in the AL Cy Young Award voting,

and eighth in the AL MVP voting.

Quisenberry had a somewhat rough September, when he went 1-2

with a 5.48 ERA and only two saves. On September 4th, he allowed six runs on seven hits and a walk

(intentional of course) in a third of an inning in a 9-5 loss to the Milwaukee

Brewers. The Brewers scored eight of

those runs in the ninth inning off of nine singles and the intentional

walk. The Royals though accomplished

what they set out to do though. They had

a total of 42 saves on their way to a 97-75 record, finishing a full 14 games

ahead of the second place Oakland A’s.

They would sweep the Yankees in the ALCS before losing to the Phillies

in six games in the World Series.

Quisenberry was excellent in the ALCS, but struggled in the World

Series, allowing six runs in 10 1/3 innings, going 1-2 with a 5.23 ERA and one

save. Overall for the season, he was

12-7 with a 3.09 ERA and a league leading 33 saves with 37 strikeouts vs. 27

walks (15 intentional) in 128 1/3 innings across 75 games. He finished fifth in the AL Cy Young Award voting,

and eighth in the AL MVP voting.

1981 wasn’t too bad of a season for Quisenberry. The strike that year really hurt him putting

up elite numbers, but it actually seemed to help him. Prior to the strike in mid-June, he was 0-3

with a 2.86 ERA and nine saves, with 11 strikeouts and nine walks (five

intentional). One of his losses came in

another five inning effort where he scattered nine hits and a walk, allowing

three runs in an 8-7 loss to the Boston Red Sox on May 4th. Sixteen days later, he lost another game,

allowing a hit and issuing THREE intentional walks in a 5-4 loss to the New

York Yankees.

After the season resumed in mid-August, Quisenberry only

allowed three earned runs the rest of the season. He went 1-1 with a 0.79 ERA and nine saves,

with nine strikeouts and six walks (three intentional). His post-strike WHIP was 0.882. The Royals made the playoffs, but they were

swept in the ALDS by the A’s. Overall

for the season, he finished 1-4 with a 1.73 ERA, with 20 strikeouts and 15

walks (eight intentional) in 62 1/3 innings across 40 games. He only allowed one home run all season.

The 1982 season began a four year span where Quisenberry was

not only one of the best relievers in the game, but one of the best overall

pitchers in the game. He carried the

second half momentum from ’81 right into April, where he pitched in seven

games, going 0-1 with six saves. He

pitched a total of 14 innings, and only faced 50 batters. That’s just eight over the minimum. By mid-season, he was 4-3 with a 2.35 ERA and

20 saves. That pace slowed a little, but

he still finished 9-7 with a 2.57 ERA and a league leading 35 saves, with 46

strikeouts and 12 walks (two intentional) in 136 2/3 innings across 72 games. It was the first season of three straight where

he walked less than a batter…per nine innings.

He made his first All Star team, finished third in the AL Cy Young

voting, and ninth in the AL MVP voting.

The Royals finished 90-72, but that was three games back of the Angels.

1983 was perhaps Quisenberry’s finest season. At the end of April, he was 1-1 with a 2.04

ERA and four saves vs. three blown saves. That was the highest his ERA would be the rest of the season, and in the other five months, he would only have four more blown saves. He was lights out in May, earning a save in all eight opportunities with a 0.46 ERA, allowing one run in 19 2/3 innings. He had two blown saves in June, but won both of those games, and added seven more saves. July saw one blown save – a game he won on July 22nd throwing a season high 5 1/3 innings in relief in the 3-2

victory of the New York Yankees. He had

his last blown save of the season on August 19th, and four days

later, he would have his last loss of the season. From August 25th on, he was

perfect in his 11 save opportunities. He

allowed four runs in three innings in a non-save situation on September 28th,

but other than that outing, he only allowed one other run in 27 1/3

innings. In those 15 games, he didn’t

walk a batter. Overall for the season,

he went 5-3 with a 1.94 ERA, with 48 strikeouts and 11 walks (two intentional)

in 139 innings across 69 games. His 45

saves destroyed the old single season record of 38 set in 1973 by John Hiller. He set career highs in saves, innings and

K/BB ratio, and career lows in ERA (other than the strike shortened 1981

season), WHIP, hits/9 and BB/9. He was

again an All Star, he finished sixth in the AL MVP voting, and finished second

in the AL Cy Young voting to LaMarr Hoyt.

Despite his efforts, the Royals finished 79-83, which was good enough

for second place, but still 20 games back of Hoyt’s White Sox.

1983 was perhaps Quisenberry’s finest season. At the end of April, he was 1-1 with a 2.04

ERA and four saves vs. three blown saves. That was the highest his ERA would be the rest of the season, and in the other five months, he would only have four more blown saves. He was lights out in May, earning a save in all eight opportunities with a 0.46 ERA, allowing one run in 19 2/3 innings. He had two blown saves in June, but won both of those games, and added seven more saves. July saw one blown save – a game he won on July 22nd throwing a season high 5 1/3 innings in relief in the 3-2

victory of the New York Yankees. He had

his last blown save of the season on August 19th, and four days

later, he would have his last loss of the season. From August 25th on, he was

perfect in his 11 save opportunities. He

allowed four runs in three innings in a non-save situation on September 28th,

but other than that outing, he only allowed one other run in 27 1/3

innings. In those 15 games, he didn’t

walk a batter. Overall for the season,

he went 5-3 with a 1.94 ERA, with 48 strikeouts and 11 walks (two intentional)

in 139 innings across 69 games. His 45

saves destroyed the old single season record of 38 set in 1973 by John Hiller. He set career highs in saves, innings and

K/BB ratio, and career lows in ERA (other than the strike shortened 1981

season), WHIP, hits/9 and BB/9. He was

again an All Star, he finished sixth in the AL MVP voting, and finished second

in the AL Cy Young voting to LaMarr Hoyt.

Despite his efforts, the Royals finished 79-83, which was good enough

for second place, but still 20 games back of Hoyt’s White Sox.

Quisenberry saw much of the same success in 1984. At the end of June, he had 20 saves and a

2.09 ERA. In the second half of the

season, he earned 24 more saves and a 3.13 ERA.

The Royals rode him hard down the stretch. In September, he was 2-0 with eight saves and

two blown saves. In 12 games that month,

he pitched 24 1/3 innings. In five of

those games, he went at least two innings.

Overall that season, he went 6-3 with a 2.64 ERA and 44 saves, with 41

strikeouts and 12 walks (four intentional) in 129 1/3 innings across 72

games. He was an All Star for the third

and final time of his career, finished third in the AL MVP voting behind fellow

reliever Willie Hernandez and Kent Hrbek, and once again he finished second in

the AL Cy Young voting, that award also going to Hernandez.

1985 would be the last year where Quisenberry would be a

dominant reliever. The first half of the

season was pretty pedestrian, at least by his standards. Through the end of June, he was 4-4 with a

2.67 ERA and 14 saves vs. five blown saves.

He gave up 65 hits and nine walks in 57 1/3 innings for a 1.291 WHIP,

but some of this may have been fueled by a .302 BAbip, which was far above his

.258 BAbip at that point in his career.

The second half of the season went a little better, as he went 4-5 with

a 2.13 ERA and 23 saves vs. seven blown saves.

He threw a total of 71 2/3 innings in 46 games in the second half. Overall, he went 8-9 with a 2.37 ERA and 37

saves, with 54 strikeouts and 16 walks (eight intentional). The Royals would finish one game ahead of the

Angels, and after beating the Blue Jays in the ALCS, they defeated the St.

Louis Cardinals in seven games to become World Series champions. That post season, he went 1-1 with a 3.00 ERA

and one save.

1985 would be the last year where Quisenberry would be a

dominant reliever. The first half of the

season was pretty pedestrian, at least by his standards. Through the end of June, he was 4-4 with a

2.67 ERA and 14 saves vs. five blown saves.

He gave up 65 hits and nine walks in 57 1/3 innings for a 1.291 WHIP,

but some of this may have been fueled by a .302 BAbip, which was far above his

.258 BAbip at that point in his career.

The second half of the season went a little better, as he went 4-5 with

a 2.13 ERA and 23 saves vs. seven blown saves.

He threw a total of 71 2/3 innings in 46 games in the second half. Overall, he went 8-9 with a 2.37 ERA and 37

saves, with 54 strikeouts and 16 walks (eight intentional). The Royals would finish one game ahead of the

Angels, and after beating the Blue Jays in the ALCS, they defeated the St.

Louis Cardinals in seven games to become World Series champions. That post season, he went 1-1 with a 3.00 ERA

and one save.

Quisenberry then decided to fall off a cliff, as far as

production went. In 1986, he went 3-7

with a 2.77 ERA and only 12 saves. He

walked 24 batters (12 intentionally) and only struck out 36 in 81 1/3 innings

across 62 games. Despite only having 12

saves, he still led the team, as the Royals only had 31 total and finished

third in the AL West. In 1987, he would

only pitch in 49 innings across 47 games and earn eight saves. He went 4-1 with a 2.77 ERA and 17 strikeouts

vs. 10 walks (three intentional).

1988 would mark Quisenberry’s last season in Kansas

City. He earned his last save as a Royal

on April 28th, and pitched his last game as a Royal on June 24th. On July 4th, he was released by

the Royals. Ten days later, he took a

trip on I-70 east, and signed with the St. Louis Cardinals. For the Royals, Quisenberry had a 3.55 ERA

over 25 1/3 innings to start the season, and for the Cardinals in July, his ERA

was actually a bit lower at 3.24 in 8 1/3 innings. Then August happened. For that month, he had a 8.49 ERA in 11 2/3

innings, and in September it was 6.00 in 18 innings. He didn’t earn a single save in the second

half of the season with the Cardinals.

Overall for the year, he went 2-1 with a 5.12 ERA and one save, with 28

strikeouts and 11 walks (three intentional) in 63 1/3 innings across 53 games.

Quisenberry somewhat righted the ship for the 1989

season. He had a rough April where he

had a 5.62 ERA in eight innings, but by the time July 6th rolled

around, he had four saves and a 1.99 ERA.

Two days later, he gave up three runs in two innings, but he wouldn’t

give up multiple runs again until his last two outings of the season, giving up

two runs each in those. For the season,

he went 3-1 with six saves, with 37 strikeouts and 14 walks (nine intentional)

in 78 1/3 innings across 63 games.

The Cardinals released Quisenberry at the end of the 1989

season. For 1990, he signed with the San Francisco Giants. This did not go well. He only pitched in five games for the Giants, all in April, before he tore his rotator cuff, which led him to retire. He gave runs in three of those games; 10 total across 6 2/3 innings. He would pitch his last game on April 23rd, giving up three runs in 2 1/3

innings in a 13-3 loss to the San Diego Padres.

Quisenberry did go out in style though.

That day, the last hit, walk, and run he ever gave up was to Joe Carter,

Jack Clark and Tony Gwynn respectively.

The Cardinals released Quisenberry at the end of the 1989

season. For 1990, he signed with the San Francisco Giants. This did not go well. He only pitched in five games for the Giants, all in April, before he tore his rotator cuff, which led him to retire. He gave runs in three of those games; 10 total across 6 2/3 innings. He would pitch his last game on April 23rd, giving up three runs in 2 1/3

innings in a 13-3 loss to the San Diego Padres.

Quisenberry did go out in style though.

That day, the last hit, walk, and run he ever gave up was to Joe Carter,

Jack Clark and Tony Gwynn respectively.

For his career, Quisenberry was 56-46 with a 2.76 ERA and

244 saves, with 379 strikeouts and 162 walks.

Of those walks, 70 were intentional.

Breaking that out, he unintentionally walked a batter every 11 1/3

innings. Quisenberry’s first balk in the

majors came on April 9th, 1988 – his 556th game in the

majors. He would end up with a total of

five. He faced a total of 4247 batters

in his career. He hit SEVEN of them. He threw four wild pitches in his career, or

one every 261 innings. As a comparison,

the best reliever of all time, Mariano Rivera, faced 5103 batters in his

career. He hit 13 of them, and threw 13

wild pitches – one every 98.7 innings.

Quisenberry had a career WHIP of 1.175, which seems a bit

high considering his lack of walks. He

was the epitome of “pitch to contact”, allowing 1064 hits in his 1043 1/3

innings. However, only 59 of those hits

left the yard, good for a 0.5 HR/9 inning ratio. Although his K/9 inning was comically low at

3.3, his low walk rate led to a 2.34 K/BB ratio. His career BB/9 ratio of 1.397 is the 20th

lowest of all time. Of the 19 pitchers

in front of him, only two pitched in the 20th century, the last one

throwing his final game in 1926.

Quisenberry had a career WHIP of 1.175, which seems a bit

high considering his lack of walks. He

was the epitome of “pitch to contact”, allowing 1064 hits in his 1043 1/3

innings. However, only 59 of those hits

left the yard, good for a 0.5 HR/9 inning ratio. Although his K/9 inning was comically low at

3.3, his low walk rate led to a 2.34 K/BB ratio. His career BB/9 ratio of 1.397 is the 20th

lowest of all time. Of the 19 pitchers

in front of him, only two pitched in the 20th century, the last one

throwing his final game in 1926.

Now that we’ve reviewed some of these numbers, I’ll let you

in on a little secret. If you know

anything at all about Quisenberry, you probably remember the almost-underhanded

delivery he had. You may assume that he

always did that, but you would be wrong.

He didn’t develop that style of pitching until spring training in

1980. His manager suggested the change

because he didn’t have a good fastball, and requested that Quisenberry learn

the style from Kent Tekulve. So not only

was Quisenberry a master control artist, he did it using a pitching style that

was totally foreign to him.

In 1996, in his first year on the Hall of Fame ballot, he

only received 3.8% of the votes and dropped off.

In 1996, in his first year on the Hall of Fame ballot, he

only received 3.8% of the votes and dropped off.

Dan Quisenberry, wherever you are, I’m not sure of your

feelings on the DONT WALK sign, but thank you for taking it to heart and

championing its cause.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)