This is the sixth edition of our Tuesday look at the

countdown to the Rookies of the Year in 1994.

This post will probably be initially depressing, but eventually, it may

end up somewhat motivational. It will

kind of be like Rocky, without any sort of success. Imagine if instead of beating Apollo Creed,

Rocky went about from sketchy gym to sketchy gym, boxing in places like

This is the sixth edition of our Tuesday look at the

countdown to the Rookies of the Year in 1994.

This post will probably be initially depressing, but eventually, it may

end up somewhat motivational. It will

kind of be like Rocky, without any sort of success. Imagine if instead of beating Apollo Creed,

Rocky went about from sketchy gym to sketchy gym, boxing in places like

Carrasco was signed as an amateur free agent out of San

Pedro de Macoris, Dominican Republic

by the New York Mets in 1988. Later

that year, he was assigned to the GCL Mets, where he would pitch in 14 games

with an 0-2 record and a 4.17 ERA to go along with 21 strikeouts vs. 13

walks. He’d have another two years of

rookie ball in Kingsport where he

would combine for a 1-6 record with a 5.55 ERA and 60 strikeouts vs. 35 walks.

Facing a sink or swim situation, Carrasco was promoted to A-

ball

Facing a sink or swim situation, Carrasco was promoted to A-

ball

For the 1992 season, the Astros assigned Carrasco to A ball Asheville ,

where he would be unawful. He would go

5-5 with a 2.99 ERA to go with 67 strikeouts vs. 47 walks and 8 saves. Still, this was not enough for him to stick

with the ‘Stros, as he would be traded with Brian Griffiths to the Marlins for

Tom Edens.

1993 would see the Marlins transform Carrasco into a starter

at A ball

1993 would see the Marlins transform Carrasco into a starter

at A ball

I guess when you change scenery enough, one of them might

work. This is what happened in 1994 with

Carrasco. Despite never making it about

A ball, he broke Spring Training with Reds.

He would make his major league debut in the Reds’ second

game of the season on April 4th, earning a win after giving up a hit

and two walks in the top of the 10th inning, and Kevin Mitchell

hitting a walk off solo shot off of the Cardinals’ Rob Murphy for a 5-4

victory. He would also get another win

in his next appearance three days later, after allowing only a walk in the top

of the 10th inning, and Barry Larkin driving in Jeff Branson to

defeat David West and the Phillies 5-4.

The formula for Carrasco’s success was clear – bring him

into games in the 10th inning when games were tied at four. That was not the case in his next appearance;

as he earned his first career save despite allowing a solo home run to the

Phillies’ Pete Incaviglia in a Reds 2-1 victory. But his next appearance was a 10th

inning victory, with the score tied at four, in

The formula for Carrasco’s success was clear – bring him

into games in the 10th inning when games were tied at four. That was not the case in his next appearance;

as he earned his first career save despite allowing a solo home run to the

Phillies’ Pete Incaviglia in a Reds 2-1 victory. But his next appearance was a 10th

inning victory, with the score tied at four, in

Carrasco had four appearances in May before a trip to the DL

would sideline him. In those appearances,

he had a couple of saves and didn’t give up a run in 5 1/3 innings with four

strikeouts vs. four walks. The Reds

didn’t seem to have a designated closer in 1994, as up to Carrasco’s last

appearance, both he and Jeff Brantley were tied for the team lead in saves.

Carrasco would rejoin the Reds on June 1st, and that

day, he would get a blown save and loss by giving up three runs without

retiring a batter in the eighth inning in a 10-9 loss to the Expos. Overall for the month of June, he was 1-3

with a 4.91 ERA, a blown save and two holds, and seven strikeouts vs. six

walks.

July would be kinder to Carrasco. He would earn a couple of saves, including a

three inning version on July 4th vs. the Florida Marlins. Overall, he was 1-2 with a 0.87 ERA, with the

two saves and a hold, and 16 strikeouts vs. 13 walks.

In the waning days of the season, across five August

appearances, he had one blown save with five strikeouts and four walks. Brantley would lead the team with 15 saves;

Carrasco was second with six. The Reds

would finish with a 66-48 record, which was good for first place in the NL

Central, and nothing else.

In the waning days of the season, across five August

appearances, he had one blown save with five strikeouts and four walks. Brantley would lead the team with 15 saves;

Carrasco was second with six. The Reds

would finish with a 66-48 record, which was good for first place in the NL

Central, and nothing else.

Over the 1994 season, Carrasco went 5-6 with a 2.24 ERA and

six saves, two blown saves, and three holds, to go along with 41 strikeouts vs.

30 walks. His ERA would not be that low

in a season for another 11 years. His

eighth place finish in the NL Rookie of the Year voting was the only time he

was voted for any honor. In 1995,

despite only pitching 87 1/3 innings, he was second in the NL in wild pitches

with 15. He was also 10th in

the NL in appearances with 64.

His 3 ½ years with the Reds would be the longest stint he

would have with any of the seven major league teams for which he played. He was traded in July of 1997 with Scott

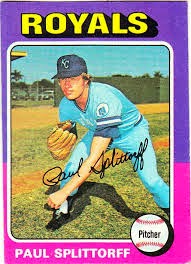

Service to the Kansas City Royals for Jon Nunnally and Chris Stynes. A 1-6 record and 5.45 ERA later, he would be

selected by the newly formed Arizona Diamondbacks as the 49th pick in the expansion draft.

His 3 ½ years with the Reds would be the longest stint he

would have with any of the seven major league teams for which he played. He was traded in July of 1997 with Scott

Service to the Kansas City Royals for Jon Nunnally and Chris Stynes. A 1-6 record and 5.45 ERA later, he would be

selected by the newly formed Arizona Diamondbacks as the 49th pick in the expansion draft. Carrasco would never pitch for the D-backs, as he would be

claimed off of waivers by the Minnesota Twins in early April 1998. He would spend 2 ½ years in the Twin Cities

before being traded to the Boston Red Sox in September 2000 for Lew Ford. Through seven games with the Sox, he had a

13.50 ERA. With

Carrasco would never pitch for the D-backs, as he would be

claimed off of waivers by the Minnesota Twins in early April 1998. He would spend 2 ½ years in the Twin Cities

before being traded to the Boston Red Sox in September 2000 for Lew Ford. Through seven games with the Sox, he had a

13.50 ERA. With

The Blue Jays would become his ninth team in January of

2001, but they released him before the start of the season at the end of

March. The Twins swooped in to sign the

known quantity a couple of days later.

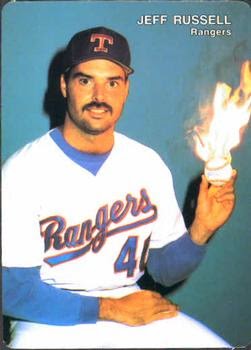

After successfully filling the bullpen that year, he was released, and

signed by team number 10, the Texas Rangers, before the 2002 season. That lasted until the end of April when he

was released. Carrasco would not pitch

in the majors at all in 2002.

Never one to know when to quit, Carrasco signed with the

Orioles for the 2003 season. After

having one of his average seasons, the Orioles ended the relationship, granting

him free agency. In 2004, for the second

time in three years, Carrasco would not pitch in the majors (although he did

pitch in

Never one to know when to quit, Carrasco signed with the

Orioles for the 2003 season. After

having one of his average seasons, the Orioles ended the relationship, granting

him free agency. In 2004, for the second

time in three years, Carrasco would not pitch in the majors (although he did

pitch in

In February 2005, Carrasco would be signed by team number

12, the Washington Nationals. This would

be hands down his best season of his career, as he went 5-4 with a 2.04 ERA

with two saves, three blow saves, nine holds, and 75 strikeouts vs. 38

walks. He would parlay that into a two

year, $5.6 million contract starting in the 2006 season with the Los Angeles

Angels of Anaheim.

Halfway through the 2007 season, the Angels released

him. He was resigned by the Nationals,

who granted him free agency at the end of the season. In 2008, he signed with the Pittsburgh

Pirates in January, who then released him in March. The Chicago Cubs signed him in May, but

granted him free agency at the end of the season. His last major league appearance came with

the Angels on

Halfway through the 2007 season, the Angels released

him. He was resigned by the Nationals,

who granted him free agency at the end of the season. In 2008, he signed with the Pittsburgh

Pirates in January, who then released him in March. The Chicago Cubs signed him in May, but

granted him free agency at the end of the season. His last major league appearance came with

the Angels on

But just because no major league team wanted him didn’t

discourage him. In 2009, at the age of

39, he played for three different independent league teams. 2010 saw him play for two more independent

league teams, as well has his Mexican League debut. In 2011, it was the same – two independent

league teams and the Mexican League.

Finally, in 2012, at the age of 42, he would play for two more Mexican

League teams before finally calling it quits.

In summary, let’s count the teams that Carrasco played for,

or was at least a part of, in his career, in the order in which he appeared:

GCL Mets (rookie Mets), Kingsport Mets (rookie Mets),

Pittsfield Mets (A- Mets), Asheville Tourists (A Astros), Kane County Cougars

(A Marlins), Cincinnati Reds, Indianapolis Indians (AAA Reds), Kansas City Royals,

Arizona Diamondbacks, Minnesota Twins, Ft. Myers Miracle (A+ Twins), Salt Lake

Buzz (AAA Twins), Boston Red Sox, Toronto Blue Jays, Texas Rangers, Ottawa Lynx

(AAA Orioles), Baltimore Orioles, Osaka Kintetsu Buffaloes (Japan), New Orleans

Zephyrs (AAA Nationals), Washington Nationals, Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim,

Columbus Clippers (AAA Nationals), Pittsburgh Pirates, Iowa Cubs (AAA Cubs),

Bridgeport Bluefish (Independent), Long Island Ducks (Independent), Newark

Bears (Independent), Shreveport-Bossier Captains (Independent), Diablos Rojos

del Mexico (Mexican), Petroleros de Minatitlan (Mexican), and Pericos de Puelba

(Mexican). That’s 31 teams by my count.

Even though he never won an official award, should the MLB

ever present a Sisyphus award, I would behighly disappointed if it didn’t have

Carrasco’s face.